Did your parish receive a white ceramic feather in 2019? How has the feather shaped your community’s engagement with Indigenous justice over the last few years? As we approach the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, how might renewed reflection on the feather inspire ongoing action?

As a professor (Sarah) and a PhD candidate (Josh) in the Faculty of Theology at Saint Paul University, we learned about the feather through our relationships with the diocese. Both of us became interested in how the reception of these sculptures could provide a unique window into how local congregations are engaging with truth and reconciliation.

During the spring and summer of 2023, we conducted our research. Travelling more than 500 kilometres, we visited 17 parishes—west to Petawawa, east to Hawkesbury, north to Wakefield, and south to Manotick. We photographed 32 feathers and 38 church buildings and interviewed 26 people, including 15 priests and 11 lay people.

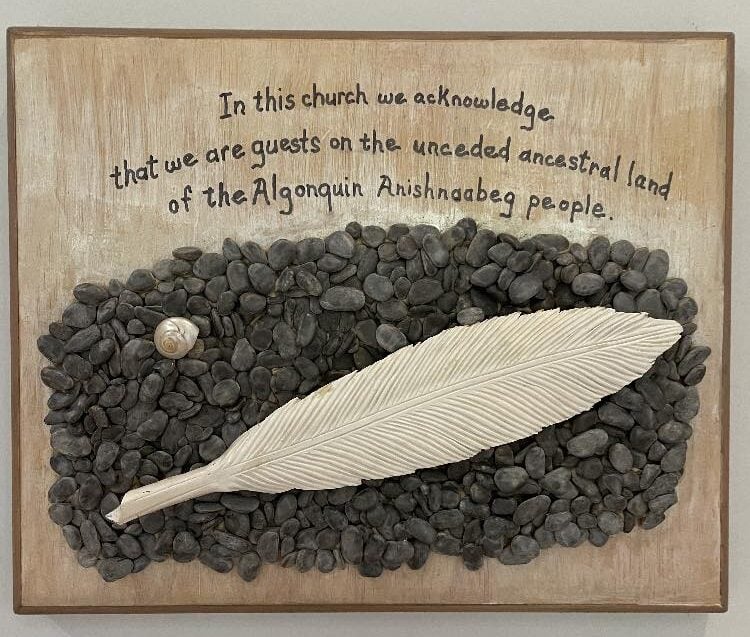

Our conversations started from the simple statement, “Tell us about the feather.” Together, we discovered how parishes decided what to do with the feather, where they placed it, how they speak and feel about its significance, and whether it is connected to other actions related to Indigenous justice. We discussed how parishes relate more broadly to matters of truth and reconciliation, such as through land acknowledgements and other liturgical practices, opportunities for learning, strengthening relationships with Indigenous peoples, and advocacy and social action. We also explored the place of the feathers in church buildings, discussing the space and other significant objects. Beyond visits to parishes, we met twice with the All My Relations circle to learn about their perspectives on the feathers and their responses to our research.

Our research on the reception of the ceramic feathers in parishes across the Anglican Diocese of Ottawa prompted us to develop a theology of “germinal ritual.” This understanding of the feathers emerged in conversation with the diocesan All My Relations circle. Although they do not use the term “germinal ritual,” they describe the feather in related ways: “[The feather] was a really good initiative to spark something, and to move things forward,” said Larry Langois, a Huron-Wendat member of the circle, “It started people to ask questions. …I think it just got a ball rolling.” Installing a work of art like the feather in the worship space, voicing a land acknowledgement, and singing a song with connections to Indigenous communities are all examples of germinal rituals that might be part of an Anglican liturgy.

Our theology of germinal ritual is inspired by research on the ceramic feathers, botanical science, ritual theory, and especially the parables that Jesus tells about seeds. We understand germinal rituals to have four characteristics. First, these ritual acts are small beginnings, like a mustard seed (Luke 13:18-19), and we cannot expect them to accomplish very much right away. Second, germinal rituals yield varied outcomes depending on context, like seed scattered in different types of soil (Luke 8:4-8), and do not guarantee certain results. Third, germinal rituals coexist with contradictory rituals, like wheat growing up alongside weeds (Matthew 13:24-20). Fourth, germinal rituals depend on human action while operating beyond human awareness, like a seed growing in secret (Mark 4:26-29), and may flourish in ways beyond human understanding and control.

Feathers occupy many different places in church buildings: inside and outside the worship space; in connection with altars, fonts, and pulpits; in relation to Indigenous symbols; and with or without written explanations. In some parishes, feathers remain in storage. Most feathers are stationary, displayed on a stand or in a frame or shadow box. At St. Thomas the Apostle Anglican Church, the feather is processed forward each Sunday in a box, held up during a land acknowledgement, placed on a stand in the chancel, and processed out at the end of the liturgy.

Studying the reception of the feathers across parishes reveals that there are a handful of parishes that both place the feather more centrally and regularly undertake action associated with truth and reconciliation such as educational events, relationship building with Indigenous people, and land-based practices like maintaining reconciliation gardens. The most active parishes are not necessarily the largest or most well-resourced parishes. But the most active parishes often have an advocate in the community for whom Indigenous justice is a priority (either a lay person or a priest), and this advocate involves others through the creation of a local leadership team. Feathers that were received in communities with this type of structure—or feathers that fostered the emergence of this type of structure—seem more likely to be linked to broader and longer term reflection and action.

For us, interpreting the feathers through a theology of germinal ritual helps push back on two common and problematic tendencies. First, it recognizes the limitations of ritual. Ritual is but one small step in a much larger transformative process. Second, it recognizes the value of ritual as one meaningful step toward social change. Ritual is not the final solution to all social issues, but neither is it irrelevant. In this way, a theology of germinal ritual can help us avoid putting either too much or too little weight on these practices. Germinal rituals should neither be abandoned nor trumpeted, but rather nurtured gently and persistently in hope.

In anticipation of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, consider how your parish may revisit the ceramic feather in new ways. Kathryn Fournier, Pinaymootang First Nation member of the All My Relations circle, said: “Maybe it’s never too late: even those congregations that got their feather—and then within a month or two it was up on the wall somewhere—and that was it, and it stayed ever since and people haven’t delved into that more.” She wonders if it is time for “Feather 2.0: What does it mean now?”

Saint Mary’s Church, Westmeath — Deanery of the Northwest