by Glenn J Lockwood

Promised Land? 1833-1880

Two years ago, the Rev. Canon Hilary Murray proposed an exhibit to celebrate Black Anglicans in the Diocese of Ottawa each Black History Month at the Diocesan Archives. At that time a series of five exhibits was proposed over five years. The 242 years that Anglicans have resided in this region were divided into five time periods:

1784-1832; 1833-1880; 1881-1928; 1929-1977; 1978-2026.

The fourth time period (1929-1977) was covered in 2022, focusing on the ordination of the Rev. Blair Allison Dixon, the first time period (1784-1832) was detailed in 2023, and this year we cover the years of struggle between 1833 and 1880.

Between 1783 and 1867, four groups of American Blacks migrated to Canada, mostly fugitive former enslaved persons. They were without wealth or power or social rank. The legacy of slavery in Canada dating back to the earliest days of New France consigned the Black migrants to labour and service roles.

It is difficult to say how many of the 40,000 Blacks in Ontario by 1867 resided in what later became the Anglican Diocese of Ottawa, as the numbers reported in printed census volumes vary wildly. The 1851 census reported 7 “Coloured persons,” the 1861 census enumerated 137, while the 1871 census counted 110 “People of African Origin” in the region that later came to be known as the diocese of Ottawa. This likely reflects the massive bias from south of the border that did not allow people taking the census to enumerate Blacks before 1870, regardless of whether they resided in slave states or free.

The frequency of Black entries in the Trinity, Cornwall parish register from the beginning of settlement indicates the massive under-reporting in the earliest printed census volumes.

Nevertheless, the years 1833 to 1880 appeared to offer promise, beginning with Britain abolishing the enslavement of Blacks in 1833 (40 years after Upper Canada proposed legislating the gradual abolition of slavery, in 1793).

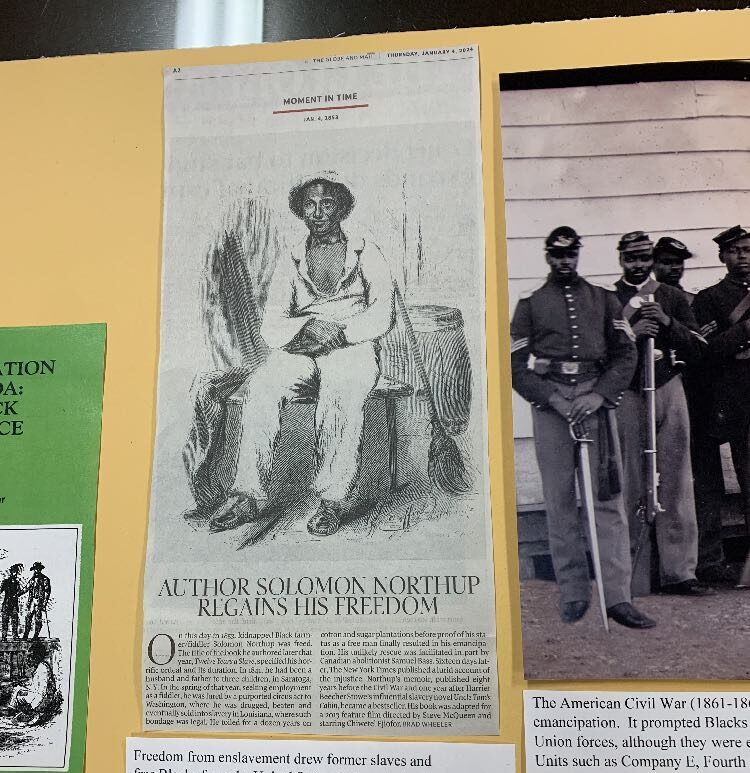

Freedom from enslavement drew former slaves and free Blacks from the United States to Canada, but the numbers arriving by way of the Underground Railroad (1834-1865) increased following the United States Fugitive Slave Act (1850) that emboldened slave owners to capture slaves who fled to free soil states. Relatively few travelling on the Underground Railroad came to eastern Ontario and western Quebec. They ended up instead in southwestern Ontario.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) held out the promise of emancipation. It prompted Blacks from 1862 to sign up with Union forces, although they were enlisted in racially segregated units such as Company E. Fourth Colored Infantry at Fort Lincoln.

In Canada, Blacks were exploited in their desperation, and they accepted wages far below those demanded by white workers. This practice attracted the enmity of white labourers, who tended to blame the former slaves for their own problems. Marginal, segregated, and dependent, the free Black group constituted a distinct caste which ranked beneath the lowest class whites.

It was their background as former slaves that was the basis for their consequent poor status in a highly status-conscious society. Ontario’s Common School Act of 1850 permitted the establishment of separate schools for Blacks. Even where such schools did not exist, Black children could be forced to attend class at separate times from whites, or to occupy segregated benches.

Saint Mary’s Church, Westmeath — Deanery of the Northwest